The first real shots of the US-China trade war have just been fired. How did it come to this, and where do we go from here?

Takeaways:

- The early 2000s were apocalyptic for the American factory worker.

- Trump is right to put some of the blame on China. Robots and other forms of work automation had a smaller impact than initially thought.

- The electoral politics of this trade war may push Trump past the point of no return.

- There’s a better way to fight for the American worker.

On May 29 the People’s Daily, China’s largest newspaper and the official mouthpiece for the central government, issued an ominous warning to the United States:

“Don’t say we didn’t warn you.”

According to CNBC, it is the same phrase the government newspaper printed before China’s 1962 border conflict with India, and the same one it ran with before China’s 1979 war with Vietnam.

The government newspaper goes on to threaten US access to a variety of economically and strategically valuable rare earth minerals. The Chinese government is signaling: Vital national interests are at stake, and we will defend them.

The US has been doing its fair share of signaling as well. Most of it is related to our trade balance with China and the wide deficit between what we buy from them versus what they buy from us. During the 2016 Republican presidential primary, Donald Trump proclaimed before the rust-belt town of Fort Wayne, Indiana:

“We can’t continue to allow China to rape our country, and that’s what they’re doing. It’s the greatest theft in the history of the world.”

Donald Trump, May 1, 2016.

Starting last summer, the Trump administration began making good on this tough talk. In 2018, the US imposed special tariffs of 10 percent on about half of all product categories imported from China, up from the 8 percent of targeted products under the Obama administration

By the time the year was out, these new tariffs applied to $250 billion of the $540 billion in goods that we imported from China in 2018. Then, on May 10, Trump dialed up the special tariff rate on most of those same products from 10 to 25 percent. This triggered the ominous reply from the Chinese newspaper.

Make no mistake. The first shots of the trade war have been fired.

How did we get here?

In a word, jobs.

The three greatest external shocks to US manufacturing employment in the last 100 years were the Great Depression of the 1930s, America’s entry into World War II in 1941, and China’s entry into the World Trade Organization (WTO) in 2001.

The contributions of the Second World War to US economic recovery following the Great Depression are generally well-understood. As America began mobilizing for war in 1940, dramatic increases in government spending and manufacturing employment provided what Paul Krugman called “the great natural experiment” in Keynesian economics.

The causes of the Great Employment Sag of the early 2000s, as economists call it, is a more contentious subject. Between 2000 and 2011, the US lost nearly 6 million manufacturing jobs.

Some economists blame automation for as much as 88 percent of these losses, noting the gap between rising manufacturing productivity yet falling job numbers.1 Factories are now about programming robots, the logic goes, and America’s blue-collar workers don’t have the skills required to keep up.

Some economists blame automation for as much as 88 percent of lost factory jobs.

More recently, however, economists have started to question this story. Manufacturing productivity figures may be significantly overstating the contribution of automation due to the curious way we count computers and other electronics.2 If you take these devices out of the equation, manufacturing productivity more closely mirrors manufacturing employment.

So if it’s not all about robots, what is this decline in factory jobs about?

Blame China?

Candidate Trump blamed countries like China and Mexico for the plight of the American factory worker.

As relates to China, President Trump has levied three specific complaints:

- Trade deficit: We buy a lot more from them then they buy from us. It’s not by accident. And it’s not fair.

- Non-tariff barriers: Although Chinese tariffs are fairly low compared to similar countries, China protects its domestic producers from US competition through other means. Foremost among them is artificially weakening its currency, the yuan, in order to keep Chinese exports cheap and foreign imports expensive. Worse, the Chinese state actively subsidizes domestic companies, allowing them to sell products below the cost of production and thus giving them further advantage over American competitors.

- Theft of Intellectual Property: As a part of doing business in China, many US companies are forced into joint ventures with Chinese counterparts. US companies report being forced to transfer technology and intellectual property that Chinese firms are then able to use to compete with us.

While there is evidence backing up each of these complaints, the merits for attacking China on parts 2 and 3 are more debatable. As Peter Beinart points out in a recent Atlantic piece, these strategies are actually quite typical of developing, middle-income countries like China as they pursue economic modernization. Indeed, many of them were adopted by the US during our own process of industrialization.

What cannot be denied is that a wide trade deficit exists between China and the United States. What evidence is there that this trade deficit is responsible for the recent loss of blue-collar factory jobs in the 2000s?

Exhibit A: China industrializes.

Just as US manufacturing employment was falling into the Great Sag, China was transforming into an economic powerhouse. Over the past 15 years, Chinese industrial output has grown from only a small fraction of global manufacturing to more than one-quarter of all production.

Exhibit B: China globalizes.

At the same time that the Chinese economy was industrializing, it was also lowering its own trade barriers and becoming more integrated into global markets. Tariff barriers against Chinese goods fell in other countries in response, especially following China’s entry into the WTO in 2001. Unsurprisingly, China’s share of world manufacturing exports rose quickly once all that industrial capacity gained access to lucrative foreign markets.

MIT Economist David Autor and his coauthors have been studying the employment shocks created by China’s rise and WTO entry. They estimate that as many as one-quarter of all US manufacturing jobs lost during the early 2000s were caused by rising import competition from China.3

They estimate that as many as one-quarter of all US manufacturing jobs lost during the early 2000s were caused by rising import competition from China.

So China is partly to blame for the desperate condition of manufacturing employment in America. The US government responded in kind, drawing us into an escalating war of rising tariffs and economic retaliation. Case closed?

Not quite.

There is one more dimension to all this bluster and brinksmanship.

In two words, job politics.

It turns out that not all parts of the US felt the pain of China’s rise equally. The same team of researchers led by David Autor discovered that some regions, especially those that specialized in furniture, toys, or sporting goods, were especially hard-hit by import competition from China.

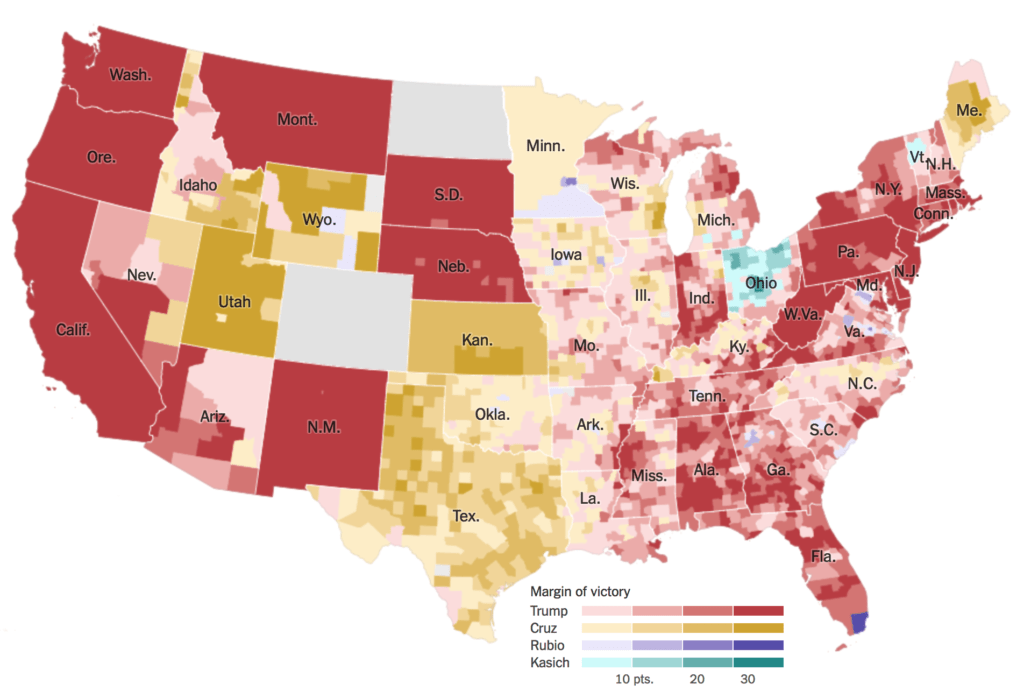

Do you notice anything peculiar about this map?

Many of the regions most affected by China’s rise are also regions that swung hard for Donald Trump and his tough talk about trade. Just look at the map of the 2016 Republican primaries.

Cruz carried his home state of Texas in the primaries, and Kasich did the same in Ohio. But many Republicans across the American South, the Midwestern rust belt, and deep into the Northeast bet on Trump.

Economic voting after all?

The book What’s the Matter with Kansas popularized the notion that low-income citizens often fail to vote in their own economic interests because they have been conned into acting based on social issues like abortion.

But now that the GOP has a leader who appears willing to take on the bad guys on trade, one can argue that what we’re seeing is a broad alignment of economic interest and political behavior.

According to a WSJ analysis of Autor’s findings, 89 of the 100 counties most affected by Chinese imports went for Trump during the 2016 Republican primary.

89 of the 100 counties most affected by Chinese imports went for Trump during the 2016 Republican primary.

The WSJ investigation zooms in on Hickory, North Carolina–a major hub for furniture manufacturing. Since the early 2000s, factories there closed and good jobs were lost. In the few places where manufacturing has managed to hold on, factory wages have stagnated or declined.

This correlation between economic hardship and political support for Trump holds up to social-scientific scrutiny,4 though other non-economic factors like racial isolation also seem to help drive the relationship.

Either way, if Trump wants to stand a chance at reelection in 2020, he would do well to earn the support of those same rust-belt voters who helped put him into office back in 2016.

That electoral calculus could be pushing America, and the world, towards a dangerous showdown with China.

That electoral calculus could be pushing America, and the world, towards a dangerous showdown with China.

Two Paths: Trade War or Trade Assistance?

There is ample evidence to back up Trump’s claim that rising import competition from China is responsible for much of the plight of the American worker.

The question before America now is whether to wade deeper into the treacherous waters of a trade war. Do we want to inflict higher prices on US consumers through more heavily taxed imports? While at the same time exposing our producers to the risk of retaliation, to say nothing of the potential unraveling of the global economy?

Such events are not without historical precedent. In 1930, just as the Great Depression was taking hold, Congress passed the Smoot-Hawley Tariff Act in an effort to protect domestic workers and producers from foreign competition. But it only encouraged America’s trading partners to raise retaliatory tariffs in response–worsening an already bad global economic crisis. In the wake of the Smoot-Hawley debacle, Congress delegated trade negotiation authority to the Executive Branch in 1934 in hopes of tempering short-sighted populist impulses.

Given Trump’s recent surprise announcement that he may levy special tariffs against Mexico starting June 10, those safeguards may be inadequate. The administration’s appetite for a politically gratifying trade war may well prove too great.

The Trump administration’s appetite for a politically gratifying trade war may well prove too great.

But there is another way forward. Rather than badgering our trading partners and risking a global tariff war, America could focus on redistributing resources from those communities that benefited most from global trade towards those that have been the most devastated.

Such a policy response would not be unprecedented. We already have public infrastructure in place in the form of Trade Adjustment Assistance (TAA)–a federal program that offers training opportunities and benefits to workers that have been hurt by import competition. This program could help workers in distressed regions retool for new jobs and even new industries in which American workers can be globally competitive.

Unfortunately, trade assistance has never even come close to providing the resources required to lift up workers and regions that have been brought down by globalization. For every $1,000 that Chinese import competition has cost the American worker, TAA spent a paltry 23 cents helping those workers adjust.

On the whole, America is wealthier for its openness to global markets. But at the same time, large numbers of Americans have been left behind. Rather than betting the house on a costly and dangerous trade war with China, it might be better to reinvest in those parts of America that have been most harmed by globalization.

Notes

- Hicks and Devaraj, 2015. “The Myth and the Reality of Manufacturing in America.”

- Houseman, 2018. “Understanding the Decline of U.S. Manufacturing Employment.”

- Autor, Dorn, and Hanson, 2013. “The China Syndrome: Local Labor Market Effects of Import Competition in the United States.”

- Autor et al., 2017. “A Note on the Effect of Rising Trade Exposure on the 2016 Presidential Election.”